Every summer, interns at Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve are given the opportunity to conduct on-site independent research projects. Working with a mentor–usually a graduate student or faculty member from the University of Minnesota–each intern (or group of interns) designs and conducts their experiment before presenting findings at an end-of-season research symposium. After a long summer in the field, Cedar Creek interns Julia Franey, Ariel Schwartzman Miles, Seamus McCarthy and Iris Cessna share their project highlights.

Can you tell me about what led to your experimental design?

Julia and Ariel: We studied the sundew populations in the Beckman Bog at Cedar Creek. Our mentor, Katrina Freund Saxhaug of the University of Minnesota, mentioned she’d seen sundew populations there in the past, but now could no longer see them from the boardwalk. This sparked our interest! Did the changing climatic conditions cause the sundews to die out in this bog, or did populations just change their location– and why? We utilized ArcGIS mapping software to track the locations of the sundew populations, allowing us to get a better idea of the shifting population dynamics. We got to go into the bog and surveyed the area, eventually finding sundew populations further into the bog, towards Beckman lake.

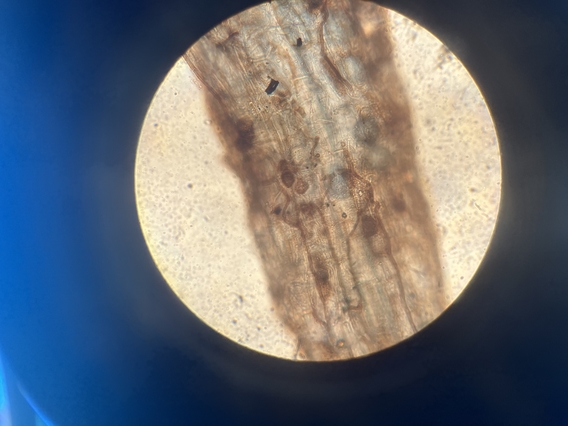

Seamus: My research was on mycorrhizal fungi–fungi that form a mutualistic relationship with plant roots–and how a particular type changes in prevalence with post-agricultural succession. Cedar Creek has a handful of abandoned agricultural fields that have been recovering from intense cultivation for different time periods. I wanted to see how the degree of arbuscular-mycorrhizal fungal (AMF) colonization changed in grass roots among these fields. To conduct the experiment, I collected soil samples and took a small amount of roots from each sample, then cleared the roots in a potassium hydroxide solution before staining them with an ink-vinegar solution. This revealed the mycorrhizal hyphae (branching body of the fungus) and arbuscules (structures unique to AMF). I examined 24 fields of view through my microscope and any view with arbuscules was noted.

Iris: For the ACE (Adaptation to Climate and Environment) experiment, bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) seeds from Minnesota, Illinois, and Oklahoma were planted in experimental sites in each of those states to compare the variable responses of seedlings to the three different climates. By planting trees from a Minnesota population in Oklahoma, we can study how the local adaptations of bur oaks create differences in their response to warmer climates. Climate change will make Minnesota’s climate more similar to Oklahoma’s modern climate, so moving the trees approximates the future climatic conditions they will experience. However, factors like the water-holding capacity of soil and surrounding vegetation can also affect bur oak seedlings.

In my first few days at Cedar Creek and at the Oklahoma experimental garden, my strongest impressions of the experiment were not about the trees themselves– they were about the stark differences in environmental conditions between and within the plots. I immediately wondered about the effect of Cedar Creek’s sandy soil on the bur oaks, the Oklahoma plot’s bright orange soil, and the dense vetch ground cover I saw in half of the Cedar Creek experimental site. These observations, and my drive to follow up on them in part because of my interest in soil sciences and geology, drove the creation of my research project.

What were your results?

Julia and Ariel: Going into this research project, only one species of sundew was recorded at Cedar Creek, the round-leaved sundew, Drosera Rotundifolia, but we noticed some obvious morphological differences between sundews in the bog.

We sent pictures to our mentor Kate Freund, who forwarded them to Rebekah Mohn of UMN, who studies the genetic diversity of Drosera. Rebekah confirmed they are two different species: Drosera intermedia being the new one! We went into the field with her and Kate to take samples for the herbarium and show her the different populations. Ideally, our findings of new sundew species at Cedar Creek will pave the way for future Drosera studies, as well as inspire others to go into the bog and make observations, as bogs are a key habitat for a wide variety of organisms, as well as good at sequestering large amounts of carbon dioxide and flood management.

Seamus: The sample size and time limits of this study make it difficult to make solid claims, but generally, older abandoned fields exhibited a greater degree of arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization than those that had been more recently abandoned. This was consistent with my hypothesis, and aligns with the fact that fungal communities are highly vulnerable to soil disturbance from plowing. What this pilot study indicates, then, is that undisturbed post-agricultural soils can recover a highly important type of soil fungi necessary for the optimal health of an ecosystem. Mycorrhizal fungi provide significant benefit to soil structure and plant physiological performance, strengthening the resilience of an ecosystem to environmental disturbance. We can use this knowledge to preserve and restore soil ecosystems which must form the basis of any farm that wants to call itself sustainable.”

Iris: I found that the presence of vetch (Lathyrus venosus) ground cover in the Minnesota garden was a much stronger predictor of seedling survival than the population the seedlings came from. Volumetric water content of the soil was also a statistically significant predictor of oak survival in the Minnesota experimental plot, but not in the Illinois or Oklahoma experimental plots, which have more soil water overall. Environmental conditions like low soil moisture will continue to affect plants as climate change progresses, so considering small-scale and large-scale environmental conditions together is essential to understanding the climate future of bur oaks, other plants, and the ecosystems they inhabit.”

Any takeaways?

Ariel: My takeaway from this experiment was really seeing how going into the field and being curious is the backbone of scientific discovery. Without my pages of scrawling field notes, I would never have examined the sundews further and noticed the gradual change in structural composition from the boardwalk to the lake (ie: two different species.) Truly, this summer showed me that science doesn't have to be an esoteric practice conducted solely in labs, but both an observation-mindfulness-based practice, as well as an adventure. One of my favorite botanists, Robin Wall Kimmerer, always says that observation rivals that of the strongest microscope. Once we learn to look around us and ask questions, make connections, and strengthen our closeness to the ecosystems that sustain us, we will forge a path of closeness to nature. I hope to come back to Cedar Creek at some point in my career and answer all my unresolved questions, formulated in Beckman bog!

Julia: Choose to study things you are excited to get up and observe every day! As young scientists, we often feel it's essential to come up with ground-breaking, multi-part, labor-intensive experiments when presented with opportunities like Cedar Creek, which is totally awesome if you feel motivated in that way, but it’s equally as important to just go out and make notes about these unique ecosystems. Ariel and I went into our project, striving to simply survey sundew populations, and our curiosity led us to find a whole new species at Cedar Creek! Therefore, I recommend anyone reading this to follow their love for science and continue to make observations about the natural world, like the many ecologists who came before us did. My summer spent at Cedar Creek, immersed in nature, was peaceful yet joyous, and I feel extremely grateful for such a beautiful experience. Therefore, I recommend anyone reading this to follow their love for science and continue to make observations about the natural world, like the many ecologists who came before us did. My summer spent at Cedar Creek, immersed in nature, was peaceful yet joyous, and I feel extremely grateful for such a beautiful experience :)

Seamus: I'd say that it's extremely important and fulfilling to learn about the knowledge held by your fellow interns and supervisors.

Iris: This experience showed me the value in my ability to think biologically and geologically simultaneously and the importance of observation to creating scientific questions. In addition to providing this new-to-me way of finding a research question, Cedar Creek was a wonderful place for me to cultivate new ways of relating to the land. From measuring volumetric water content at dawn, to weekend bike rides, to eating wild berries with my breakfast most mornings, my activities of living, learning, and observing my environment have never been so tightly enmeshed with a place as during my time at Cedar Creek.