Plants were a constant for Alejandra Perez-Enriquez growing up in Sarapiqui, Costa Rica, a rural area 60 miles northeast of the capital city of San José with a landscape defined by rivers and rainforests. “Our house and backyard were always full of plants,” she says. “My mom and grandma kept medicinal plants. They know the forest. That got me interested in tropical ecology.”

Now a graduate student advised by Plant and Microbial Biology Professor Jennifer Powers, Perez-Enriquez studies how plants interact with the environment. She makes regular trips back to Costa Rica for field research and to work on ecological restoration projects in conjunction with an organization she started with a fellow student while still an undergraduate.

A pioneering approach

The organization is called Guarumo, a nod to a tree common to the region known for its tendency to be first on the scene in areas where there’s been a disturbance to the environment. It also provides food and shelter to critical species. Perez-Enriquez sees an affinity between the role this “pioneer tree” plays in ecosystems and the role the organization plays in restoring them. Within conservation circles, ecological restoration has become a priority in recent years. The United Nations launched its Decade on Ecosystem Restoration in 2021. Engaging local people in the process is something new.

“Ecosystems are not isolated from us. We are part of them,” says Perez-Enriquez. It’s a deceptively simple statement given the complexities involved in the kind of collaborative, grassroots approach called participatory ecological restoration championed by Guarumo. Since its inception in 2019, the organization’s staff has grown from two to seven coming from diverse backgrounds from ecology to teaching to social science. “We know we need to do ecological restoration and we need to do it with the people,” she says. “It was less common to bring the community into the process when we started out, so we saw ourselves a little like guarumo tree.”

Place as palimpsest

Landscapes are not static. They evolve and traces of the past — both visible and invisible — continue to shape the present. Perez-Enriquez describes this dynamic state as a palimpsest, a term with literary roots used in this case to describe the layers of natural and human history that leave their mark on a place. Participatory ecological restoration relies on the people who know the landscape best to create a picture of what has been, what is and what might yet be.

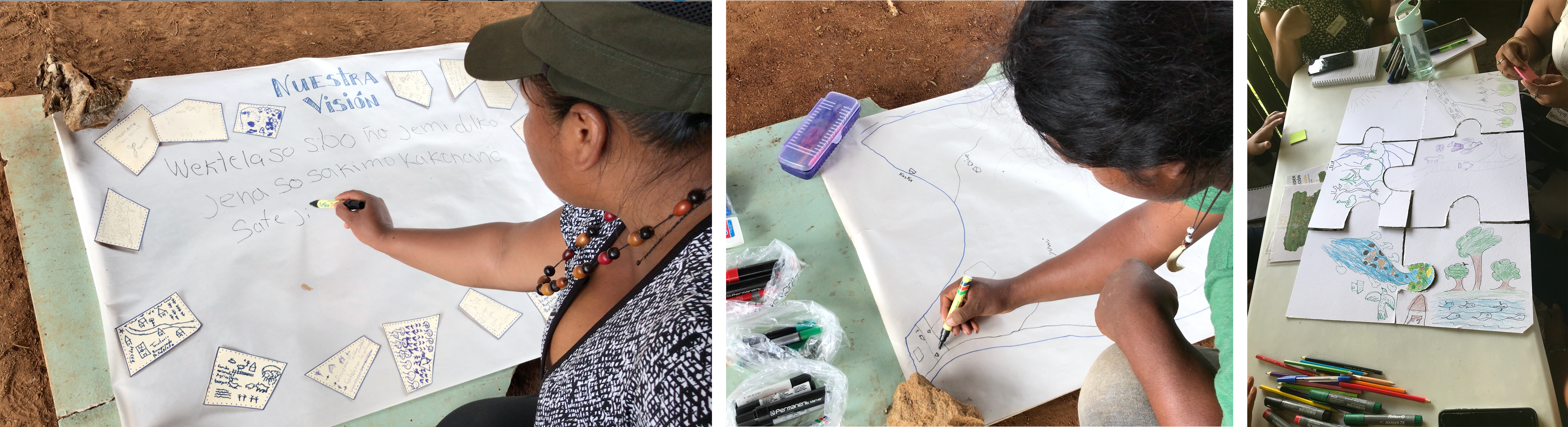

Perez-Enriquez and her colleagues employ a technique called participatory mapping to understand a particular environment and the community’s relationship to it. She describes drawings as a common language that can transcend linguistic and cultural barriers. Members of the community draw features of the landscape as it is, as it was and as they wish it to be. They share information about the connections between plants, animals and people. This, in turn, helps inform the recommendations Perez-Enriquez and her colleagues make about a specific place, bringing together the scientific and the social to develop detailed ecological restoration plans.

Perez-Enriquez notes making room for people to explore the power they have to shape their future is a much-needed corrective to a past marked by colonialism and the disenfranchisement of the local people. “We haven't ever been part of the decisions made about the land,” she says. “When we do ecological restoration in this way, we have the power to decide how the land is going to be.” –Stephanie Xenos

Members of the Cabecar nation in China Kicha share their vision for the community and draw a map of the stolen land recovered by the community to identify historical disturbances and opportunities for restoration culminating in the creation overlaid on puzzle pieces representing the objectives for restoration.